Albania

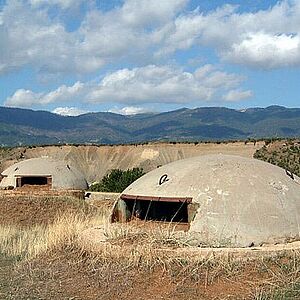

Misuse of Transitional Justice

The regime under Enver Hoxha is said to have built 170,000 bunkers like this one in Albania – stone witnesses to a national communism under a leader who believed he was surrounded by enemies. After more than four decades of dictatorship, in the mid-1990s Albania became a pioneer in addressing its own past. But Robert C. Austin and Jonathan Ellison note in their study that the process soon came to a halt. They had already identified the problem in 2008: the political parties were exploiting the issue [...Read more]

![[Translate to Englisch:] ISKK](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/1/csm_20150824_182137_ISKK_bea_7351532423.jpg)

The Long Shadow of the Hoxha Regime

A picture from better times: Agron Tufa, director of the Institute for Studies on Communist Crimes and Consequences (ISKK), is photographed with his staff and a foreign guest. After receiving several death threats, he resigned from his post in 2019 and applied for asylum in Switzerland. The incident is symptomatic of how Albania has dealt with its communist past, writes historian Idrit Idrizi in his analysis of the transitional justice discourse in the Balkan state. It all began with a book: In [...Read more]

Compensation with Obstacles

An owner re-plastered the outer wall of his apartment building – but only where it adjoins his own home. The picture shows the difficulties of establishing a functioning market economy in Albania after a decades-long state-controlled economy. Compensating the victims of the expropriations still poses problems for the Albanian state today, a topic analyzed in a study by the legal scholar Romina Kali. The first thing the Communist Party did after it took power in Albania was to expropriate the large [...Read more]

Argentina

![[Translate to Englisch:] Fotos Verschwundener in der Gedenkstätte Rosario [Translate to Englisch:] Bildaufnahmen von Opfern der argentinischen Militärjunta](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/3/csm_1024px-Desaparecidos_Rosario_7_Ausschnitt_2_ae1d4338b8.jpg)

The Long Struggle for Recognition

The word “Desaparecido” (Disappeared) appears beneath the photos displayed by victims’ relatives in the former police prison of Rosario. It is followed by the portrayed person’s date of arrest. Human rights activists estimate that 30,000 people disappeared after their arrest. The Swiss historian Alexander Hasgall has analyzed the arduous struggle to have them recognized as victims of the military dictatorship. His thesis: One reason their struggle was successful was because it allowed society to [...Read more]

![[Translate to Englisch:] Prozess gegen die Junta-Mitglieder [Translate to Englisch:] Gerichtsprozess gegen Angehörige der argentinischen Militärjunta](/fileadmin/_processed_/7/f/csm_Juicio_a_las_Juntas_bearb_ebb454546f.jpg)

In Search of Justice

The former members of the military junta look serious as they enter the courtroom in Buenos Aires in May 1985. Five of them received long prison terms in December. But in 1990, President Carlos Menem had them pardoned – a decision that would be reversed twenty years later. Human rights experts Pär Engström and Gabriel Pereira have studied the process of criminal justice in Argentina. They speak of an “ebb and flow in the search for justice.” For a long time, those responsible for serious human [...Read more]

Cambodia

Hoping for Justice

Kaing Guek Eav, the former head of the S-21 prison, stands in a prison uniform before the special court in Cambodia. Prosecutors, judges and defense attorneys from all over the world attended, listening to translations via headphones. It took a long time to establish the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal was officially called. When it finally commenced its work in 2006, many analysts saw it as a reason for hope. In light of its modest achievements, it is [...Read more]

Buddhist Peacebuilding in Cambodia

Monks dressed in orange are a natural part of street life in Cambodia. But they were killed in large numbers under the Khmer Rouge, which believed that to build a new society, religious ties – along with all cultural traditions – had to be destroyed. In spite of this, after communism came to an end, the patriarch of Cambodian Buddhism spoke out against punishing the perpetrators. An essay describes Maha Ghosananda’s unusual approach to dealing with the past. In an anthology on “post-secular world [...Read more]

Chile

The Power of the Military

Armed to the teeth, two members of the Chilean national police force are waiting for their deployment at a student demonstration in Santiago de Chile at the end of 2019. The Carabineros have a bad reputation with human rights organizations. In 1973 they joined the putschists without hesitation; their commander was a member of the military junta. One year later, the police were placed under the Ministry of Defense, where they remained until 2011. A 2004 essay by the Hamburg security expert Michael [...Read more]

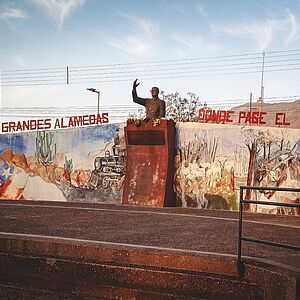

Reconciliation or Transitional Justice?

The socialist president Salvador Allende stands with his hand raised in front of a mural in the Chilean community of Palmilla. His term of office, which was accompanied by strikes, demonstrations and a severe economic crisis, continues to polarize Chileans to this day. After the end of the military dictatorship, Patricio Aylwin, the country’s first democratically elected president, wanted to reunite society. But the victims demanded punishment for the perpetrators. An essay describes the dichotomy [...Read more]

Ethiopia

![Tiglachin monument in Addis Ababa [Translate to Englisch:] Tiglachin-Denkmal für äthiopische und kubanische Soldaten in Addis Abeba](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/a/csm_Statue_at_Tiglachin_Memorial_10ba814e97.jpg)

A Missed Opportunity

How can a change of regime take place without leading to despotism and anarchy? The concept of transitional justice was developed for the transition from authoritarian rule to democracy. Jima Dilbo Denbel, director general of the Ethiopian Agency for Civil Society Organizations, examined a case study (published in English) on transitional justice in Ethiopia. According to the author, during a regime change, instead of focusing solely on the prosecution of perpetrators, it is important to take into [...Read more]

![Mengistu Haile Mariam [Translate to Englisch:] Ein offizielles Bildnis des äthiopischen Diktators Diktator Mengistu Haile Mariam](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/b/csm_800px-NME7007_65acee2c5a.jpg)

An Epoch of Permanent Significance

The Red Terror represented a period of intense political and inter-communal violence in revolutionary Ethiopia in the late 1970s. This is the conclusion drawn by the British Africa-historian Jacob Wiebel in his study on the start of the communist military regime at the Horn of Africa. The violence erupted two years after the revolution of 1974 and was concentrated in the cities of Ethiopia, particularly in Addis Ababa, Gondar, Mekele, Asmara and Dessie. In the struggle over the direction of the [...Read more]

Georgien

The practice of compensatio

The scene is reminiscent of the Soviet Union: while the “Father of Nations” is celebrated on the top floor of the Stalin Museum in Gori, a replica of a prison cell is presented beneath the stairs. This is how the museum has commemorated the victims of the communist dictatorship in Georgia since 2010. Although the victims are legally entitled to assistance, in practice they receive little help. A study by the Institute for the Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI) analyzed their [...Read more]

When Injustice Return

A guard patrols from the observation tower of Prison No. 8 in Tbilisi. The prison in the Gldani district made international headlines when videos of prisoners being tortured were published shortly before the parliamentary elections in 2012. These turned out not to be isolated cases. In a detailed report, the International Center for Transitional Justice made suggestions on how to address these human rights abuses. The man that U.S. Senator Hillary Clinton suggested as a candidate for the Nobel [...Read more]

Germany

Can We Learn from History?

The artist Gunter Demnig has laid 75,000 “Stumbling Stones” in Germany and many other European countries since 1992. It has become the largest decentralized memorial in the world. The brass-coated stones commemorate victims of National Socialism. For a fee they are set into the ground in front of the former homes of the victims. They can now be found in 1,265 German municipalities. While remembrance of the crimes committed under National Socialism remains important to Germany, historians are [...Read more]

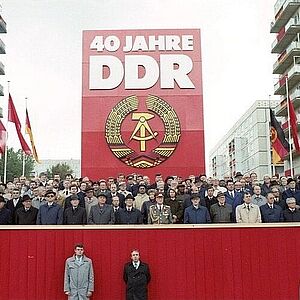

Germany’s “Second” Past

The end of the GDR came as a surprise to most people. As late as October 7, 1989, the SED politburo in East Berlin attended a flamboyant parade in honor of the GDR’s 40th anniversary. Just ten days later, SED Secretary General Erich Honecker was forced to resign. The following year, on October 3, 1990, the GDR officially joined the Federal Republic. The downfall of the socialist dictatorship created the need for a reappraisal of Germany’s “second” past that became a subject of fierce controversy. [...Read more]

A Day of Liberation

No speech by a German president is quoted more often than the one delivered by Richard von Weizsäcker during a memorial service in the German Bundestag in May 1985. Its key sentence read: “May 8 was a day of liberation. It liberated all of us from the inhuman system of National Socialist tyranny.” In retrospect, it seems paradoxical that he, of all people, ushered in a turning point in Germany’s remembrance culture: In the late 1940s he had helped defend his father, who was convicted of crimes [...Read more]

What does working through the past mean?

In April 1945, a German woman is led by U.S. soldiers to the dead bodies of prisoners from the Buchenwald concentration camp. The horror over Nazi barbarism is written all over her face. But how sustainable was this form of “re-education” – the term used by the Western Allies for their political education program for Germany? In an essay in 1959, the Marxist-inspired philosopher and sociologist Theodor W. Adorno accused the Germans of wanting to draw a line under their past. The text with the [...Read more]

Peru

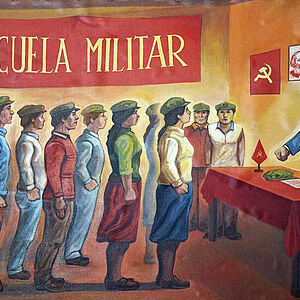

Compensation – but how?

The propaganda image of the "Shining Path" calls for people to enlist in the armed struggle. Poverty and discrimination against the indigenous rural population provided fertile ground for the recruitment of its more than 23,000 members. Social assistance therefore played an important role in the discussion over providing compensation to victims. Two anthropologists studied the implementation of reparations programs. According to estimates made by the Truth Commission, nearly 70,000 people were [...Read more]

The Problem of Internally Displaced Persons

In the photo, a village community carries eight coffins to the grave. The picture was part of the Peruvian Truth Commission's "Yuyanapaq" exhibition. The years of armed conflict caused more than death and injury. Many residents fled to the big cities to escape the violence. A UN consultant describes their situation in the slums of Lima – and makes suggestions on how the government could help them. While many violent conflicts cause large numbers of people to flee to neighboring countries, Peru [...Read more]

Russia

Why a reappraisal of the Stalinist era is so difficult

Once a year, the victims of the “Great Terror” are commemorated in a remote forest in Karelia. Here, in Sandarmorch, almost 10,000 people were buried between October 1937 and December 1938. In the general public, however, where Stalin's terror receives little attention, the dictator continues to be regarded as a great statesman. Historian and human rights activist Arseny Roginsky, who died in 2017, explains in an essay why coming to terms with the past in Russia is so difficult. For a long time, [...Read more]

Gulag Memorials in Russia

The "Wall of Mourning" in Moscow is six meters high and thirty meters long. On October 30, 2017, the day of remembrance for the victims of political violence in Russia, the massive monument was inaugurated in the heart of the capital by Russian President Vladimir Putin. This long-standing demand by Memorial, an organization engaged in reappraisal of the past, for a monument had thus been fulfilled. But the organization’s representative, Irina Sherbakova, criticized the monument as “disingenuous.” An [...Read more]

Rwanda

![Memorial at the Butare University [Translate to Englisch:] Plakat und Blumengebinde in der Gedenkstätte der Universität Huye-Butare](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/3/csm_1200px-thumbnail_Genocide_Memorial_at_National_University_of_Rwanda_-_Huye__Butare__cbe8a0c5a1.jpg)

Genocide Does not Fall under the Statute of Limitations

"The light will eventually overcome the darkness of genocide.” These are the words on the banner of the memorial at the university in Butare, the cultural center of the country near Kigali. Nearly 250 such memorials commemorate the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. But the country in Africa is far from democratic states. In an article from 2018, the peace and conflict researcher Julia Viebach draws mixed conclusions on the country’s efforts to come to terms with its past. In the early 1990s, Rwanda was [...Read more]

![International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda [Translate to Englisch:] Internationaler Strafgerichtshof für Ruanda in Arusha](/fileadmin/_processed_/e/f/csm_1280px-Ictr_office_3_in_Arusha_bearb_f12890f7dc.jpg)

An Important Signal

Following the genocide in Rwanda, the International Criminal Tribunal (ICTR) issued exactly 75 sentences. Given the estimated 200,000 murderers and at least 800,000 murder victims, this is a very small number. This is why the Rwanda government decided to have lay courts (Gacaca) in the villages judge the accused. This procedure met with criticism because it was often not possible to guarantee the rule of law. In spite of this, in a study by the Swiss Institute of Federalism, the lawyer Lea Tanner [...Read more]

South Africa

![[Translate to Englisch:] Desmond Tutu](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/4/csm_tutu_at_trc_2_26dd3bb899.jpg)

Disillusionment Instead of Healing

Desmond Tutu, the Archbishop of Cape Town, looks contentedly into the audience at a hearing of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The Nobel Peace Prize winner was appointed chairman of the commission by Nelson Mandela. Its work sparked strong interest, and not just in South Africa. Outside the country, many experts examined this attempt at engaging victims and perpetrators in a dialogue as a way to heal past wounds. The first academic thesis on the Truth and Reconciliation [...Read more]

![[Translate to Englisch:] Soweto township](/fileadmin/_processed_/2/9/csm_Soweto_township_bearb_01_de65c7ad41.jpg)

Ecotherapy against Black-on-Black Violence

The corrugated iron shacks on the outskirts of Johannesburg stretch on endlessly. They formed a separate city under the name Soweto until 2002. It is less well known that in the early 1990s, the townships around Johannesburg were the site of bitter battles between Blacks. Stephanie Schell-Faucon studied a project that tried to use a form of ecotherapy to reconcile the leaders of opposing groups. Katorus is a township agglomeration located 50 kilometers south of Johannesburg. In 1993 and 1994, [...Read more]

Taiwan

Transitional Justice in Taiwan – Change and Challenges

The memorial in the former military prison of Taipei has taken great measures to restore the former laundry. Under martial law, prisoners were forced to work here. Since the election victory of the opposition Progress Party in 2016, the process of coming to terms with the past has experienced a noticeable upswing in Taiwan. In 2019 two young Taiwanese scientists compiled a summary of what has been achieved so far and they encourage further research. The authors Nien-Chung Chang-Liao and Yu-Jie [...Read more]

Transition without Justice

There were around 43,000 statues of Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan in 2000. Previously situated in the city of Kaohsiung, they now stand in a “memorial garden” next to the dictator's mausoleum in the country’s northwest. With its damage only visible at second glance, it serves as a symbol for how Taiwan's recent history is being addressed. In an essay from 2005, the author Naiteh Wu draws a critical balance. Coming to terms with the past is a difficult process that continues to divide the Taiwanese [...Read more]

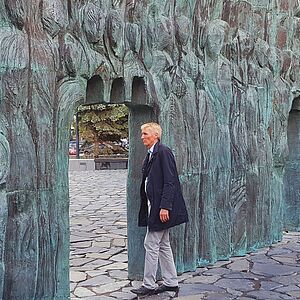

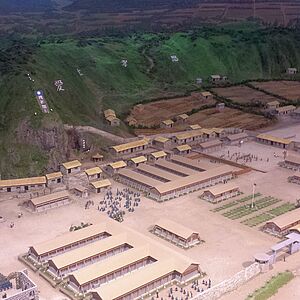

Reconstructed Unity History

The mountain slopes appear like a natural wall, enclosing the “New Life” correctional center on Green Island. A model on the grounds of the memorial shows the position of the barracks and guards’ accommodations. The Taiwanese architectural historian H. W. Lin has conducted a detailed analysis of the memorials in the remembrance park dedicated to the White Terror of 2015. The author has been working for many years on sites linked to prominent events. In her opinion, former torture and detention [...Read more]

Tunisia

Learning from Tunisia

The larger-than-life portrait of the Tunisian dictator Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali is taken down. After his overthrow in 2011, human rights activists and politicians worked to achieve transitional justice. They were advised and supported by foreign partners. In September 2018, political scientist Mariam Salehi analyzed why transitional justice in Tunisia came to a standstill. “Tunisia is a paradigmatic case of how transitional justice is currently being implemented. After the fall of the regime of [...Read more]

How the Truth Commission fell Victim to the Parties

Hearings were an important instrument in Tunisia’s transitional justice process. The Commission for Truth and Dignity put twelve public hearings on the Internet. On March 31, 2019, after five years of work, it presented its final report. Yasmine Jamal Hajar used this occasion to describe how the work of the Commission had been appropriated and complicated by the Tunisian parties. “The 17th of November 2016 is a notable date in the modern history of Tunisia. The Truth and Dignity [...Read more]

Truth and Justice

In May 2014, the journalist Sihem Bensedrine became chair of the nine-member Commission for Truth and Dignity in Tunisia. Its task was to investigate human rights violations since 1955. Her work was supported by regional offices, committees and a ministry of transitional justice. While the moderate Islamist Ennahda Party focused on compensating the victims, secular forces were more concerned with criminal investigations and historical research. In an article from November 2014, political scientist [...Read more]

Transitional Justice – The Example of Tunisia

The architecture of the huge party headquarters of the Tunisian state party RCD was meant to underscore its power. But the party was banned in March 2011, just shortly after the revolution. The political fragmentation of society has complicated efforts to address the last 50 years of dictatorship. Personnel changes only took place at the top of the state institutions. And very few of those responsible have been brought to justice under criminal law. Two and a half years after dictator Ben Ali fled, [...Read more]

Ukraine

Lustration in Ukraine

Maidan Nezalezhnosti - Independence Square in Kiev is the most famous square in Ukraine. In 2004, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians gathered here for the “Orange Revolution.” Ten years later, the square again became the scene of protests when the “Euromaidan” movement forced a profound political change. In 2016, political scientist Evgenija Lezina evaluated how successful the demonstrators were in achieving their demand for fundamental change within the political elite. Unlike most countries of [...Read more]

From Lenin to Lennon

On February 21, 2014, the Soviet dictator Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was toppled – not the actual person, but his effigy, which stood in the recreational park of the industrial city of Khmelnytskyj. In several waves since independence, more than 5000 Lenin monuments were removed in Ukraine. In 2015, a law required not only the removal of Communist symbols but also the renaming of Soviet street names. Political scientist Maksym Y. Kovalov has studied this process of decommunization. The author begins his [...Read more]