The books in the Chilean Human Rights Museum documenting the horrors of the Pinochet dictatorship resemble books on an altar. They are based primarily on the findings of two government committees: the Rettig and the Valech Commissions. The process of coming to terms with the past in Chile has also been carefully observed by the international world. Although many analyses exist in German and English, only a few are freely accessible on the internet.

Reconciliation or Transitional Justice?

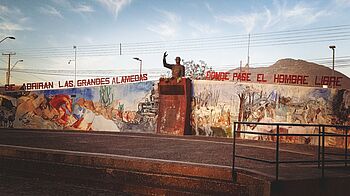

Credit: Paula López Romero / CC BY-SA

The socialist president Salvador Allende stands with his hand raised in front of a mural in the Chilean community of Palmilla. His term of office, which was accompanied by strikes, demonstrations and a severe economic crisis, continues to polarize Chileans to this day. After the end of the military dictatorship, Patricio Aylwin, the country’s first democratically elected president, wanted to reunite society. But the victims demanded punishment for the perpetrators. An essay describes the dichotomy between transitional justice and reconciliation.

In an anthology on Chile in 2004, the German-Chilean social scientist Norbert Lechner and his colleague Pedro Güell describe the difficulties in confronting the past in their country. According to a survey conducted in 1986 – when the dictatorship still existed –71 percent of the respondents thought that the human rights violations were a real problem. Of these, 59 percent agreed that those responsible for them should be punished following a fair trial. But at the end of the military dictatorship, the situation looked very different.

Efforts to confront the past crimes were limited as long as the former dictator Augusto Pinochet remained commander-in-chief of the army. Furthermore, in 1978, the military ensured through an amnesty law that most crimes be declared exempt from punishment. Only Pinochet’s arrest in London in 1998, following a Spanish extradition request, put the issue back on the agenda – and caused what the authors call a “break into the past.” But when the British authorities released the ex-dictator after a year and a half of house arrest, he was welcomed by enthusiastic supporters in Chile.

Against the backdrop of a divided Chilean society, the authors analyze the handling of Pinochet’s military dictatorship. For them, memory is always a “social construction” since the socio-political context determines how collective memory deals with the past. Their conclusion: “In every society there is a more or less explicit policy of coming to terms with the past, which provides the power framework within which (or against which) society works out what it remembers and forgets.”

Click here for the text by Norbert Lechner and Pedro Güell

Links

Report from the Commission on Truth and Reconciliation

Report from the Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture (Spanish)

The New York Times on the report from the Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture

Inter Press Service on the report from the Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture

After the Dictatorship. Instruments of Transitional Justice in Former Authoritarian Systems – An International Comparison

A project at the Department of Modern History at the University of Würzburg

Twitter: @afterdictatorship

Instagram: After the dictatorship

With financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

The Power of the Military

Armed to the teeth, two members of the Chilean national police force are waiting for their deployment at a student demonstration in Santiago de Chile at the end of 2019. The Carabineros have a bad reputation with human rights organizations. In 1973 they joined the putschists without hesitation; their commander was a member of the military junta. One year later, the police were placed under the Ministry of Defense, where they remained until 2011. A 2004 essay by the Hamburg security expert Michael Radseck shows how strong the military in Chile was for a long time -- and how much it hindered efforts to come to terms with its past role.

“Even on the eve of their seizure of power on September 11, 1973, Chile’s armed forces had a reputation for being an exceptionally professional force. Unlike most of their South American brothers in arms, the Chilean uniformed troops were considered, if not depoliticized (Dahl 1971: 50), then at least demonstrating a certain tradition of restraint and neutrality towards politics (Nohlen 1973: 181). Against the backdrop of the longest military rule on the subcontinent after Brazil, this formerly positive attribute has long become negative. In allusion to its (constitutional) legal and factual position, Chile’s military today is regarded on the one hand as a state within the state, and on the other as a fourth power within the state.” Continue reading (German)