Visitors study documents in the Peenemünde Historical-Technical Museum. The largest military research center in Europe was located here during the Nazi era. Since World War II, the twelve years of Nazi rule have been the focus of countless academic studies – receiving far more scholarly attention than any other historical epoch. But the time of GDR has also been intensively researched. Reappraising the past has itself become a subject of historical research.

Credit: Hubertus Knabe

Can We Learn from History?

Credit: Axel Mauruszat

The artist Gunter Demnig has laid 75,000 “Stumbling Stones” in Germany and many other European countries since 1992. It has become the largest decentralized memorial in the world. The brass-coated stones commemorate victims of National Socialism. For a fee they are set into the ground in front of the former homes of the victims. They can now be found in 1,265 German municipalities. While remembrance of the crimes committed under National Socialism remains important to Germany, historians are beginning to question whether it actually helps prevent history from being repeated.

In an essay from January 2020, historian Martin Sabrow questions the point of reappraisal efforts in general. His thesis: “The awareness of having learned from the past has turned the absurd assumption that history offers us lessons to we should take to heart so that we become immune from repeating the past into a quasi-religious article of faith that gives the politics of our time its ultimate value-based justification across party lines.” Sabrow’s view is based primarily on the rise of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party, but he also criticizes the reappraisal of the GDR past, which he says took place “in a parallel world.”

Sabrow is director of the Leibniz Center for Contemporary History Potsdam (ZZF), the successor institution to the GDR Academy of Sciences. He was chairman of a commission named after him that was established by the red-green coalition government in 2005 to create the historical network “Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship.” At the time, the commission’s proposals were harshly criticized by experts and ultimately rejected by the CDU’s Minister of Culture and Media, Bernd Neumann, in 2006.

Click here for the essay by Martin Sabrow (in German).

Links

Website of the Historic-Technical Museum Peenemünde

Website of the Stumbling Stones Coordination Office in Berlin

Website of the Leibniz Center for Contemporary History Potsdam

The Institute for Contemporary History’s criticism of the Sabrow Commission’s recommendations (German)

Historian Hubertus Knabe’s criticism of the Sabrow Commission’s recommendations (German)

After the Dictatorship. Instruments of Transitional Justice in Former Authoritarian Systems – An International Comparison

A project at the Department of Modern History at the University of Würzburg

Twitter: @afterdictatorship

Instagram: After the dictatorship

With financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

Germany’s “Second” Past

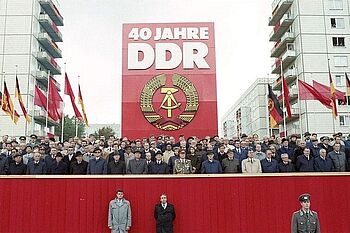

The end of the GDR came as a surprise to most people. As late as October 7, 1989, the SED politburo in East Berlin attended a flamboyant parade in honor of the GDR’s 40th anniversary. Just ten days later, SED Secretary General Erich Honecker was forced to resign. The following year, on October 3, 1990, the GDR officially joined the Federal Republic. The downfall of the socialist dictatorship created the need for a reappraisal of Germany’s “second” past that became a subject of fierce controversy.

The need to extend the reappraisal of the past to include communism was met with resistance, especially from the leftist political camp. Until then, even the leading research on the GDR had regarded the SED state as a legitimate alternative order. The SED State Research Association that was founded at Free University of Berlin in 1992 understood both the GDR and the Third Reich to be totalitarian forms of rule. The question of whether and to what extent National Socialism and Real Socialism were comparable was not the only issue to invite prompt discussion. The question of how to address sites of persecution that had been used by both regimes also led to debate. The memorial site directors of the former concentration camps of Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen, as well as others, were faced with the challenge of how to depict two dictatorships at the same place and at the same time.

The formula introduced by the West German historian Bernd Faulenbach in 1991 during discussions to develop a new concept for memorial sites in the state of Brandenburg led to a kind of minimal consensus: “Post-war injustices must not be used to relativize Nazi crimes, but these later injustices must also not be trivialized in view of the crimes committed by the Nazis.” This principle was later adopted by the German Bundestag’s Enquete Commission on the Reappraisal of the History and Consequences of the SED Dictatorship. It could not, however, prevent the debate on how to deal with Germany’s “double” past from flaring up time and again.

In 1994, in an essay on “coming to terms with the past after totalitarian rule in Germany,” the political scientist Eckhard Jesse made the case for a comprehensive approach. He predicted that the term “totalitarianism” would become more accepted. Furthermore, he advocated for a lasting delegitimization of the former power apparatus of rule and asserted that despite all its difficulties, Germany’s success in dealing with its past was better than its reputation.

Click here for Jesse’s text (in German, registration necessary).

A Day of Liberation

Credit: Telford Taylor Papers, Arthur W. Diamond Law Library, Columbia University Law School, New York, N.Y. : TTP-CLS: 15-2-2-160. / Public domain

No speech by a German president is quoted more often than the one delivered by Richard von Weizsäcker during a memorial service in the German Bundestag in May 1985. Its key sentence read: “May 8 was a day of liberation. It liberated all of us from the inhuman system of National Socialist tyranny.” In retrospect, it seems paradoxical that he, of all people, ushered in a turning point in Germany’s remembrance culture: In the late 1940s he had helped defend his father, who was convicted of crimes against humanity at a war crimes trial in Nuremberg.

On May 8, 1985, three days after U.S. President Ronald Reagan visited Germany, the German Bundestag met for a memorial service commemorating the 40th anniversary of the German surrender. A wreath-laying ceremony at a military cemetery in Bitburg attended by German Chancellor Helmut Kohl had just caused a public debate when it was disclosed only shortly before the visit that members of the Waffen-SS were also buried at the cemetery. Von Weizsäcker’s speech was therefore also understood as an “answer to Bitburg.” Kohl, however, had previously spoken of a “day of liberation.”

Although von Weizsäcker’s speech was met with criticism – primarily from his own party, the CDU – and although historians saw in it an unhistorical reinterpretation that turned the German capitulation into liberation, his credo soon advanced to become a kind of “raison d’état” for the Federal Republic. Only ten years later, the then German President Roman Herzog invited the victorious powers to join Germany in a celebration of the 8th of May in Berlin. On the 60th, 70th and 75th anniversaries, the subsequent German presidents also delivered speeches similar in tenor to that of Weizsäcker’s. In 2020, politicians from the Greens, SPD, Left Party and FDP campaigned to have May 8 declared a new public holiday: “The Day of Liberation.”

Click here for von Weizsäcker’s speech.

What does working through the past mean?

Credit: Cpl. Edward Belfer / Public domain

In April 1945, a German woman is led by U.S. soldiers to the dead bodies of prisoners from the Buchenwald concentration camp. The horror over Nazi barbarism is written all over her face. But how sustainable was this form of “re-education” – the term used by the Western Allies for their political education program for Germany? In an essay in 1959, the Marxist-inspired philosopher and sociologist Theodor W. Adorno accused the Germans of wanting to draw a line under their past.

The text with the simple title “What does working through the past mean?” introduced a change in the way National Socialism was addressed. After its publication, the idea of being able to come to terms with the past was increasingly replaced by the concept of an ongoing reappraisal process. The Institute for Contemporary History in Munich played an important role in implementing this concept. After the GDR came to an end, the institute that had been founded in 1949 opened an office in Berlin.

Click here for Adorno’s text.