The room in the Moscow Gulag Museum, in which the terror apparatus in the Soviet Union is addressed, resembles a futuristic command post. Even experts have difficulty finding their way through the ramified and frequently restructured agency. Although there are many analytical examinations of the Stalinist past, few scientific studies exist on the country’s process of coming to terms with its past.

Credit: Hubertus Knabe

Why a reappraisal of the Stalinist era is so difficult

Credit: Hubertus Knabe

Once a year, the victims of the “Great Terror” are commemorated in a remote forest in Karelia. Here, in Sandarmorch, almost 10,000 people were buried between October 1937 and December 1938. In the general public, however, where Stalin's terror receives little attention, the dictator continues to be regarded as a great statesman. Historian and human rights activist Arseny Roginsky, who died in 2017, explains in an essay why coming to terms with the past in Russia is so difficult.

For a long time, Roginsky was the best-known face of the human rights organization Memorial. He co-founded the organization during the Soviet era in 1988 and was imprisoned from 1981 to 1985 for his work as the editor of an underground magazine. His father had also been a prisoner in a Gulag camp. In his text, published in 2009, Roginsky reviews the state of historical reappraisal in Russia and analyzes why the image of Stalin in opinion polls continues to be positive.

According to Roginsky, the most important obstacle hindering a functioning memory of terror is the inability of Russians to disassociate the evil in the way other nations do. In other countries, people can identify with the victims or resistance fighters, but in Russia, distinguishing between perpetrators and victims is very difficult. Moreover, no state legal act or confidence-inspiring court decisions exist that clearly identify the state terror as a crime. A third point is that the Soviet terror was directed primarily against its own people, making it difficult to comprehend. Thus, in Russia, the victims are remembered, but the perpetrators do not feature largely in the collective memory.

Unlike in earlier decades, awareness of the Stalinist era is no longer shaped by people’s personal memories, but instead by collective images of the past. And these are strongly influenced by the politics of memory pursued by political elites who in the 1990s sought to legitimize themselves on the basis of Great Russia’s “glorious” past. Strong focus was placed on Stalin’s victory over Nazi Germany, causing the memory of his terror to shift to the background.

These factors also determined how the culture of memory is practiced in Russia. More than 800 monuments and memorial plaques exist. But because the crimes and the people who committed them are not acknowledged, those who suffered persecution appear more like victims of a natural disaster. The monuments are not the work of the central state, but instead instigated by civic groups or local institutions and are often located in remote places, such as at the mass graves from the Stalinist era. In the city centers, many streets are still named after the people who initiated the terror.

Another cornerstone of commemoration is formed by the almost 300 regional books of remembrance containing the names of more than one and a half million victims. A database that Memorial published on the internet includes more than 2.7 million names.1 But this represents only a fraction of all victims. The Russian state has mostly stayed clear of this work, which is why the record of the names remains inconsistent. Of the more than 300 mass graves of victims who were shot, more than 200 have yet to be found. None of the buildings where the terror was planned or carried out, nor any of the canals, railroads or factories built by prisoners, are marked as places of remembrance.

Roginski notes that the 300 or so local museums do address the terror, but almost exclusively in the context of the respective region’s industrialization process. The more recent school history books mention Stalinism as a system, but they present the terror as historically necessary and inevitable. This perspective does not exclude sympathy for the victims, but it does suggest that state power embodies something higher than law and morality or the interests of the individual. “The state is always right - as long as it can handle its enemies” - this idea pervades textbooks from beginning to end, writes the historian in his essay that has been translated from Russian.

Click here for the complete text by Arseny Roginski.

- The Memorial database now contains more than three million names.

Links

Analysis of motherhood and survival in the Stalinist Gulag

Analysis of children and teenagers in the Gulag

The Question of the Perpetrator in Soviet History (restricted access)

Stalin’s Terror and the Long-Term Political Effects of Mass Repression

The Great Terror in Leningrad: A Quantitative Analysis

After the Dictatorship. Instruments of Transitional Justice in Former Authoritarian Systems – An International Comparison

A project at the Department of Modern History at the University of Würzburg

Twitter: @afterdictatorship

Instagram: After the dictatorship

With financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

Gulag Memorials in Russia

Credit: Hubertus Knabe

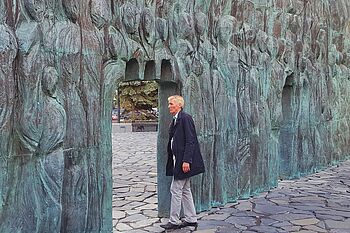

The "Wall of Mourning" in Moscow is six meters high and thirty meters long. On October 30, 2017, the day of remembrance for the victims of political violence in Russia, the massive monument was inaugurated in the heart of the capital by Russian President Vladimir Putin. This long-standing demand by Memorial, an organization engaged in reappraisal of the past, for a monument had thus been fulfilled. But the organization’s representative, Irina Sherbakova, criticized the monument as “disingenuous.” An essay from 2007 analyzes the origins and forms of Gulag memorials in Russia.

According to cultural scientist Natalia Konradova, the first monument dedicated to the victims of persecution in the Soviet Union was erected in 1988 in Vorkuta - an industrial town north of the Arctic Circle that had been built largely by prisoners. The monument, originally intended merely as a placeholder for a larger memorial, consists of a large stone wrapped in barbed wired on top of a column. Several more monuments were established in 1989, including one on Solovetsky prisoner island.

In 1990, as the communist system was rapidly disintegrating, a memorial stone was also erected in front of the KGB headquarters in Moscow. This stone, too, was originally intended as a “foundation stone” for a larger monument and its placement there was rather incidental. The stone had first been set next to the monument dedicated to Feliks Dzierżyński, the founder of the Soviet secret police, but that statue was moved to another location a short time later. The idea of placing an unhewn rock at a site as a first step was also adopted in other places, such as Arkhangelsk, Saint Petersburg and Barnaul in Siberia.

According to the author, victim commemoration in Russia was mostly improvised at first. It was always initiated by organizations engaged in the reappraisal of the past and local authorities. Most of the memorials were dedicated in the early 1990s. By the end of the decade, public commemoration efforts had subsided. Numerous monuments were also erected by representatives of nationalities persecuted under Stalin, especially from Poland and the Baltic states.

When more than a commemorative stone was desired, monuments tended to be modeled after the countless war memorials in Russia. An example of this is a monument erected in the village of Abez' in the Komi Republic in 1989, in which a military stele serves as the basis for a wreath made of barbed wire. The similarity to the formal language of war memorials is even more obvious in a memorial erected in Khanty-Mansiysk in 1997. A red wall there bears the inscription “To the victims of repression” and is framed by the dates “1937-1942.” The names of the people who were killed are listed on the side walls alongside a bowl with a flame. The only variation from a classic war memorial is the large cross at the spot where a sculpture of a soldier would normally be found.

Crosses often served as design elements elsewhere as well. Sometimes these were ordinary grave crosses, such as in a monument erected in the village of Ust'-Nera in the Republic of Yakutia. More often, however, these monuments differed from traditional cemetery crosses, such as in the village of Abez' where a cross is formed by recesses in a metal “flame.” In the village of Jagodnoe near Magadan, a cross is formed out of two handcuffed hands. These kinds of distorted crosses are found elsewhere, too. Today, however, Christian iconography has become more prevalent at many memorial sites where the Russian Orthodox Church’s is active.

A wall or a stone with a crack or fracture running through it is another common design element. This symbolism is also employed in more recent monuments to fallen soldiers of the Russian army. In contrast, monuments dedicated to the victims of Stalinist persecution often feature the motif of blank space, usually in the form of a cross or a human figure, such as on the “Wall of Mourning” in Moscow. The blank space is an allusion to the earlier practice of cutting out or blacking out arrested family members from photographs in private photo albums so as to avoid being classified as “enemies of the people” when a search was conducted.

At the end of her article, which is accompanied by black-and-white photographs, the author recalls the demand for a central memorial, which was still unfulfilled at the time of publication. She sees in it a symbol for a reassessment of Russian history. She also references another memorial in Moscow, which consists of stone heads locked behind a metal grid in a concrete wall. According to the author, this little-known monument loses its poignancy, however, because it is not situated in public space, but instead in a Moscow sculptural garden - next to heroes from children's books, copies of war memorials and that very Dzierżyński monument that was removed from the city center in 1991.

Click here for the entire essay (restricted access).

Links

Reconciliation with – or rehabilitation of – the Soviet past (restricted access)

Comparison of transitional justice in Russia and Serbia

Post-Soviet Hauntology: Cultural Memory of the Soviet Terror (restricted access)

Decree on establishing a monument for the victims of political repression (Russian-German)