"No matarás" (Thou shalt not kill) is written on the poster in the "Place of Memory" in Lima. And yet for so long, killing was the order of the day in Peru. Scholars have noted critically that since the violence mainly affected the poorest of the poor, the process of coming to terms with this past was only half-hearted. Politicians and the military often denied their share of responsibility and the state was reluctant to pay reparations.

Credit: Adrián Portugal / CC BY-SA 4.0

Compensation – but how?

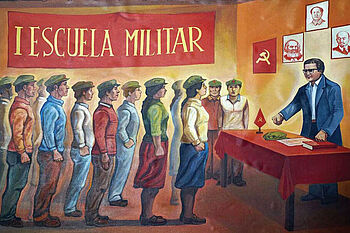

The propaganda image of the "Shining Path" calls for people to enlist in the armed struggle. Poverty and discrimination against the indigenous rural population provided fertile ground for the recruitment of its more than 23,000 members. Social assistance therefore played an important role in the discussion over providing compensation to victims. Two anthropologists studied the implementation of reparations programs.

According to estimates made by the Truth Commission, nearly 70,000 people were killed in Peru between 1980 and 2000; up to 600,000 were displaced from their homes. In its 2003 final report, the Commission made extensive proposals for individual and collective reparations. The program attached to the report is considered the most comprehensive in Latin America – but only parts of it have been realized.

In 2005, Law No. 28592 came into force, according to which victims of armed violence were to be compensated individually. A reparations council and a victims' registry were created to implement this. At the same time, plans were made to compensate social inequalities through collective aid and to grant more rights to marginalized communities. The young anthropologists Ivan Ramírez Zapata and Rogelio Scott-Insúa describe the Peruvian approach to reparations programs as both "narrow" and "comprehensive."

Using two case studies, the authors show that mixing the two approaches led to a number of practical problems. For example, Peru adopted a housing program for people who had lost their homes to destruction or other violence. More than 44,000 individuals filed claims through the Victims Registry. But the requests were handled by the Ministry of Housing under an existing assistance program called Techo Propio (Own Roof), which allowed only those whose income did not exceed a certain limit to receive assistance. Recipients were also not allowed to have mortgaged their property or own land elsewhere. According to the authors, it was not the human rights violation but the social situation that was decisive in determining whether someone received the benefit.

A large number of previously recognized victims were thus excluded from the program. When deciding who should benefit from the aid, it was no longer the damage suffered in the past that counted, but rather the current material situation. Those victims who had helped themselves, either by taking out a loan or improving their income, were effectively "punished" for doing so. "Thus the figure of the victim was gradually dissolved into the world of the economically vulnerable population that needed state subsidies, and it became commonplace to find victims who had been part of Techo Propio long before their registration into the Official Registry of Victims," the authors note.

Their second case study concerns aid to displaced persons. As a result of Law No. 28223, a registry for displaced persons was established in 2006 at the Ministry for Women and Social Development, with more than 60,000 enrollments. In 2007, the registered names were transferred to the Victims Registry, which was created somewhat later. The problem, however, was that no individual compensation whatsoever was provided for displaced persons. The Collective Reparations Program instead provided community support for devastated communities and groups of displaced persons in cities. As a result, many registrants found that they had hastily registered under a victim category that did not benefit them personally. Well-organized indigenous communities that had been victims of displacement were also significantly more likely to benefit from collective assistance than individual displaced persons. "This leaves displaced persons who cannot or do not wish to be part of an organization without a way of obtaining reparations," the authors conclude.

Click here for the entire study (restricted access).

Links

Guidelines for the Collective Reparations Program (Spanish)

Guidelines for the Collective Reparations Program (machine-generated translation)

After the Dictatorship. Instruments of Transitional Justice in Former Authoritarian Systems – An International Comparison

A project at the Department of Modern History at the University of Würzburg

Twitter: @afterdictatorship

Instagram: After the dictatorship

With financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

The Problem of Internally Displaced Persons

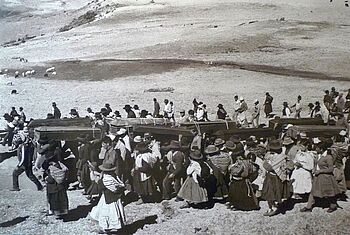

In the photo, a village community carries eight coffins to the grave. The picture was part of the Peruvian Truth Commission's "Yuyanapaq" exhibition. The years of armed conflict caused more than death and injury. Many residents fled to the big cities to escape the violence. A UN consultant describes their situation in the slums of Lima – and makes suggestions on how the government could help them.

While many violent conflicts cause large numbers of people to flee to neighboring countries, Peru faces the problem of so-called internal refugees. Of the 600,000 refugees, about 200,000 live in urban slums on the outskirts of Lima alone. In an analysis published in 2009, Gavin David White, who advised them on behalf of the UN, criticized that their living conditions had improved little since their arrival.

Most of the refugees still live in the same makeshift shacks that were built when they arrived. Drinking water is only available from trucks, which is seven times more expensive than tap water. On average, they have to work more than 14 hours a day in street trading and temporary work to make ends meet. Many of them do not speak Spanish – they know only the indigenous language Quechua – and a considerable number are illiterate.

In his essay, White points out that the influx of migrants into urban centers continued even after the violence ended. He attributes this to the poor living conditions in rural areas. Without improvements in the education system and livelihoods, this is unlikely to change, he argues. Despite the increased presence of government institutions in the interior and some progress in access to water sources and education, there is still a huge gap between urban and rural areas.

White therefore argues for the development of small businesses in Lima's slums that would simultaneously benefit the displaced and the rural areas. As examples, he cites the importation of citrus products for the production of fruit juices, which are not available in the capital, or the production of household cleaning products using natural derivatives from the interior. "Importantly, such structures can benefit both rural and urban IDP communities, contributing towards both slum regeneration and rural economic development," White points out. In this way, they would contribute to increased economic activity among the poor, which would promote further economic development – thus reversing migration flows.

Click here to read the entire analysis.