An exhibition room in the "House of Leaves" in Tirana. The drawings on the back wall show various torture techniques. Only a handful of scholars have conducted in-depth research on the communist dictatorship in Albania. Because of language barriers, there are hardly any international specialists. Most of the analyses addressing the process of transitional justice in Albania are published in English.

Credit: Leonie Buche

The Long Shadow of the Hoxha Regime

![[Translate to Englisch:] ISKK](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/1/csm_20150824_182137_ISKK_bea_81f7523553.jpg)

Credit: Hubertus Knabe

A picture from better times: Agron Tufa, director of the Institute for Studies on Communist Crimes and Consequences (ISKK), is photographed with his staff and a foreign guest. After receiving several death threats, he resigned from his post in 2019 and applied for asylum in Switzerland. The incident is symptomatic of how Albania has dealt with its communist past, writes historian Idrit Idrizi in his analysis of the transitional justice discourse in the Balkan state.

It all began with a book: In April 2019, the ISKK published a documentary on crimes committed by communist partisans during World War II. In turn, a socialist party deputy accused ISKK director Tufa of besmirching the heroes of the anti-fascist resistance and demanded his dismissal. Tufa countered by pointing out that the deputy had sentenced people to death as a judge during the communist dictatorship. Other public figures began speaking out, calling Tufa "sick," "ignorant" and "fascist." In October 2020, the governing parties decided to prohibit the institute from investigating Albanian history before 1944.

In his essay published in 2021, historian Idrit Idrizi explores the question of why thirty years after the demise of the communist regime, dealing with its legacy in Albania still sparks feud-like polemics among political and intellectual elites. He identifies three key factors: first, the division of society under the Hoxha regime into people with "good" and "bad" biographies; second, a still widespread way of thinking in categories of friend-foe with a mentality of violence; third, a decades-long system of spying that shattered the Albanians' trust in social relations.

In the rest of the text, Idrizi outlines how efforts to address the past were politically instrumentalized at an early stage. For instance, in response to dwindling support, the Democratic Party (DP) passed laws on criminal prosecution and lustration in 1995. It soon became clear, however, that both laws were intended primarily to exclude leading Socialist Party (SP) politicians from the upcoming elections. In 1996, the DP won an absolute majority in an election that was deemed fraudulent, only to lose again the following year after the so-called Lottery Uprising. The SP, which was then in power, overturned the most important transitional justice measures.

In 2005, the DP returned to power and again attempted to use a lustration law to clean up the state apparatus. But the law was overturned by the Constitutional Court on the justification that the law would allow for judges and prosecutors from the communist era to be dismissed without proof of their personal guilt. Since returning to power again in 2013, the SP, under the influence of foreign organizations, has made several efforts to address the past, including opening the Sigurimi files. But the ruling party's position has remained ambiguous and inconsistent, Idrizi writes. The main interest of the DP, on the other hand, continues to be personally vilifying political opponents for their personal or family ties to communism. The debate about the past, the author concludes, has been hijacked by the two major political parties, who have instrumentalized the issue for their own purposes.

Click here for the entire text by Idrit Idrizigeht.

Links

Historian Idrit Idrizi on private memories of communism in Albania (p. 85-102)

After the Dictatorship. Instruments of Transitional Justice in Former Authoritarian Systems – An International Comparison

A project at the Department of Modern History at the University of Würzburg

Twitter: @afterdictatorship

Instagram: After the dictatorship

With financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

Compensation with Obstacles

An owner re-plastered the outer wall of his apartment building – but only where it adjoins his own home. The picture shows the difficulties of establishing a functioning market economy in Albania after a decades-long state-controlled economy. Compensating the victims of the expropriations still poses problems for the Albanian state today, a topic analyzed in a study by the legal scholar Romina Kali.

The first thing the Communist Party did after it took power in Albania was to expropriate the large landowners. In the summer of 1945, it distributed their land to dispossessed peasants. Only three years later it pursued a course of collectivization during which it reclaimed the land from them again. The other sectors of the economy were also nationalized and the Albanian constitution stipulated that only the state was allowed to own real estate. The victims of this comprehensive expropriation often lost not only their property, but also their freedom and sometimes even their lives.

After the end of the communist dictatorship, Albania faced a double challenge: how to privatize a large part of the economy and also provide compensation for politically motivated expropriations. In 1991, Law 7501, titled "On Land," transferred land back to the peasants who had last farmed it. In her study, legal scholar Romina Kali explains this decision by pointing out that the many voters in the countryside were politically more important to the government than the interests of the former landowners. The Albanian state also distributed real estate to its citizens without considering that it may have been unjustly confiscated. According to Kali, this approach led to major societal conflicts.

Law 7698, titled "On the Restitution and Compensation of Property to Former Owners," followed two years later. According to this law, the original owners were entitled to restitution or full compensation for their confiscated property. An administrative commission was established to make decisions on the claims. But according to Kali, the Albanian state was not in a position to pay this much compensation. The monetary payments were therefore later replaced by the transfer of other property, for example in the cities. The law was also poorly drafted, as it did not provide for application deadlines or a court of appeal.

Consequently, the decisions made by the Compensation Commission led to numerous lawsuits. In the process, the legal basis changed several times because the law was repeatedly amended and supplemented by other laws. As a result, the process of privatization, restitution and compensation lacked transparency, was undemocratic and inconsistent. According to the author, the unsatisfactorily resolved ownership issue also presents an obstacle to negotiating Albania’s integration into the European Union.

Click here for the essay by Romina Kali (pp. 6-29).

Links

Study on the (non-)rehabilitation of former politically persecuted persons in Albania

Historian Adelina Nexhipi on the political transformation process in Albania

OSCE study on how Albanians view their country’s communist past

The Political Scientist Jonila Godole about Transitional Justice in Albania

Misuse of Transitional Justice

Credit: Marc Morell / CC BY-SA 3.0

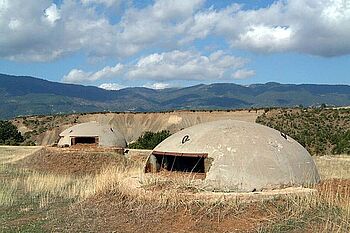

The regime under Enver Hoxha is said to have built 170,000 bunkers like this one in Albania – stone witnesses to a national communism under a leader who believed he was surrounded by enemies. After more than four decades of dictatorship, in the mid-1990s Albania became a pioneer in addressing its own past. But Robert C. Austin and Jonathan Ellison note in their study that the process soon came to a halt. They had already identified the problem in 2008: the political parties were exploiting the issue for their own gain.

"Lustration went awry because it was introduced to achieve other goals." The two experts use this quote from Arben Imami, former Albanian Justice and Defense Minister, to illustrate early attempts to initiate a process of de-communization in Albania. Their text offers an overview of the transitional justice measures taken in the 1990s, when the country played a pioneering role in the Balkans in regard to this issue.

Because Albania experienced one of the harshest forms of communism in Europe, it should have been obvious, according to the authors, that there were compelling reasons for the country to engage in an intensive confrontation with its past. But one need know little about the Albanian transitional leaders’ biographies to understand that this was not going to happen.

After briefly outlining the Hoxha dictatorship, the authors turn their attention to the early embezzlement trials against leading party functionaries. They proceed to describe the lustration and file inspection laws introduced in 1995. In their view, the Democratic Party exploited these laws for its own interests, which is why they were quickly eliminated after the Socialist Party's returned to power in 1997.

The authors describe the process of coming to terms with the past in Albania as disorganized and politicized. Left and right-wing parties have used it as a means to maintain power and a weapon in the political struggle. This winner-takes-all attitude, they write, was reinforced by the experience of class struggle under communism that included routine purges and an intolerance for opposition leaders. The authors conclude: "What we experienced in Albania was primarily politically motivated revenge rather than an attempt to deal constructively and objectively with the past."

Click here for the essay by Robert C. Austin and Jonathan Ellison