"Martín Roca Casa" is written on a brochure on display at the Place of Remembrance in Lima. This is the name of a student who was arrested after a demonstration in 1993 and presumably killed at the Peruvian army headquarters. His parents testified before the Truth Commission in 2002. Their report and numerous others have since been made available online by the museum's Research and Documentation Center.

Credit: Johnattan Rupire / CC BY-SA 4.0

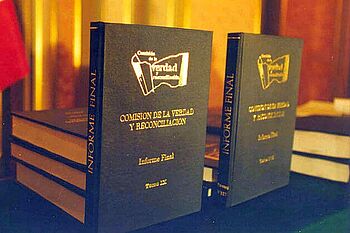

Documentation of Terror

The final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was handed over to Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo in August 2003, is 6000 pages long. It describes in detail massacres, murders, attacks, kidnappings, torture and sexual violence in Peru in the 1980s and 1990s. The authors of the nine-volume documentary subsequently received death threats and libel suits.

The Commission, appointed in June 2001, had two years to investigate tens of thousands of acts of violence. Under its chairman, philosophy professor Salomón Lerner Febres, it collected more than 15,000 witness statements, located more than 4,600 gravesites and identified nearly 24,000 victims by name. Based on a projection, it concluded that there were 69,280 violent deaths between 1980 and 2000, most of them in the Ayacucho region, which is inhabited predominantly by indigenous ethnic groups. In 47 cases, the commission proposed criminal investigations.

The Truth Commission's report is the most comprehensive account of the internal Peruvian civil war to date. While the first volume provides an overview of events, the second analyzes the armed individuals. The third volume addresses the responsibility of politics, the judiciary and social organizations. Four additional volumes depict the murderous events in detail: violence in the regions, typical events and types of crime, and 73 cases investigated in greater detail by the Commission. Finally, volume eight describes the factors that facilitated the violence, while volume nine provides recommendations for reform and a reparations program.

Unlike in many other countries, the public response to the report was mixed. Conservative politicians and the media in particular objected to the characterization of the conflict with the Shining Path as an "internal armed conflict.” They argued that this would give the "terrorists" the status of combatants. The Commission's claim that the violence committed by police and soldiers did not represent individual excesses but was part of a systematic practice was also met with criticism, especially from the parties responsible for it and the security forces. In a heated debate, the Commission was even accused of sympathizing with the Shining Path. Death threats and – unsuccessful – libel suits by military officers were the result.

However, a look at the conclusions, which are also available in English, shows that the Commission took great pains to reach a balanced judgment. Both the security forces and the parties responsible at the time are expressly thanked for their efforts. The decision of the Shining Path to begin armed struggle is identified as the "immediate and fundamental cause" of the conflict’s outbreak. The Commission also concludes, however, that "grave, massive human rights violations were perpetrated in combat against subversive groups," for which "elected civilian governments incurred the most serious responsibility."

In 2019, Peruvian economist Silvio Rendón published a study in which he estimated the number of dead at 48,000, much lower than the Commission’s estimate. He said that the Peruvian state, not the Shining Path, was responsible for the majority of these deaths. In a reply, Rendón was accused of methodological errors, which made his approach inferior to that of the Truth Commission.

Click here for the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Spanish). Its conclusions are found here.

Links

Website of the Research and Documentation Center CDI (Spanish)

Website of the Peruvian Truth Commission (Spanish/English)

Historian Jaymie Heilman on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Peru

After the Dictatorship. Instruments of Transitional Justice in Former Authoritarian Systems – An International Comparison

A project at the Department of Modern History at the University of Würzburg

Twitter: @afterdictatorship

Instagram: After the dictatorship

With financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development