Millions of people spent years of their lives in camps or in exile in the Soviet Union. But for decades, speaking publicly about this was forbidden. It took until the late 1980s for memoirs to begin to be published in large numbers. There are only a few Gulag survivors in Russia today and their experiences no longer receive much public attention.

Credit: Hubertus Knabe

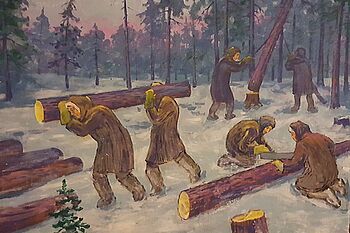

"Our daily rations depended on the amount of work accomplished”

Credit: Hubertus Knabe

The Gulag prisoners were forced to do hard physical labor in freezing temperatures. This wood cutting scene was captured by the painter Adam Schmidt, who was also imprisoned in a camp. The Jewish-Polish jurist Dr. Jerzy Gliksman described how the system of forced labor was organized in the Soviet Union in the late 1940s. His report for a United Nations Commission of Inquiry is one of the first eyewitness reports on the Gulag.

In spite of the fact that the work was beyond the limits of our endurance, we all strained to the utmost to perform it as best we could. This was partly to avoid the jeering advice and mocking remarks of the section leaders and supervisors; but mainly in order to obtain more food. For the size of our daily rations directly depended upon the amount of work every one of us accomplished on any particular day. It was the general policy to keep all in a state of semi-starvation and to give individual prisoners a chance to better their rations as a reward for better work. Hunger was thus made to serve to increase the level of production.

Even the smallest task in camp had its pre-determined and carefully computed ‘norm.’ Special tables stated the amount of all possible kind of work that a camp inmate was required to do in a day. These quotas foresaw the amount of boards a prisoner was to plane, the number of square meters of ground he was to clear, how many nails he was to drive, or what tonnage he had to load or unload. The norms were very high. Even an exceptionally strong laborer would have had great difficulty in filling them, and we, the perpetually hungry and weak slave workers, found the task utterly impossible.

The worst off were those who filled less than 10% of their daily norm. Those were considered otkaschiki, that is, people refusing to work at all. Such an individual was put in a penal chamber (the ‘isolator’) where he received only some water and 300 grams of bread a day. As a further punishment he was also brought to court and sentenced anew.

Not much luckier were prisoners who executed only between 10% and 30% of their assigned work. They too received only 300 grams of bread a day, but in addition were allowed some unshortened watery soup from the ‘penal pot.’ I was extremely careful not to fall into this category, for those who once suffered this misfortune—and there was a great number of prisoners who did—were lost forever. After a few days of such semi-starvation, these people became weaker and weaker and their working capacity thus kept decreasing. These unhappy individuals were consequently never again capable of the greater amount of work, which would enable them to raise their status to that of a higher category and cause them to obtain an additional piece of bread; a vicious circle indeed! We could see these people shrinking before our eyes...

Click here for the report from Jerzy Gliksman (English, pp. 53-57).

Links

Short biography of Jerzy Gliksman

Jerzy Gliksman’s book “Tell the West"

After the Dictatorship. Instruments of Transitional Justice in Former Authoritarian Systems – An International Comparison

A project at the Department of Modern History at the University of Würzburg

Twitter: @afterdictatorship

Instagram: After the dictatorship

With financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

"What I Saw and Learned in the Kolyma Camps"

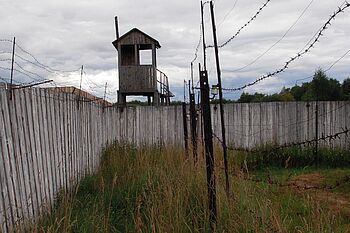

Credit: Wulfstan, CC BY-SA 4.0

Watchtowers, palisades, barbed wire – that is how most Soviet labor camps looked. The only largely preserved camp is located near Perm. The “Gulag Archipelago” became famous primarily through the book of the same title written by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who spent eight years of his life in various labor camps. Many other authors have also described the terror of the Stalinist era. The best known among them are Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam and Varlam Sharlamov, none of whom lived to see the end of the communist dictatorship.

When Alexander Solzhenitsyn published the novella “A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” in the Soviet literary magazine Novy Mir in 1962, it caused a sensation. It was the first time the daily life of a camp prisoner was described in a state publication - with the personal approval of party leader Nikita Khrushchev. But the thaw came to an end in 1964 under Khrushchev's successor Leonid Brezhnev. When Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970, he was unable to accept the prize in person for fear of not being allowed to return afterwards. A year later, the KGB attempted to poison him. When the first part of his “Archipelago Gulag” appeared in the West in 1976, he was arrested and expelled from the country.

The major work of another writer was not published in its entirety until after the collapse of the Soviet Union: “What I Saw and Learned at the Kolyma Camps” by Varlam Shalamov. The author is considered the most important chronicler of the Gulag. He spent a total of 18 years in Soviet labor camps. As a student in 1929, he had circulated Lenin's political testament, which proposed replacing Stalin as general secretary. The 1600-page book contains more than 100 stories and six cycles. Although parts could only be published in the West in 1971, Shalamov tried to avoid confrontation with the Soviet rulers. He died in a mental hospital in 1982. On a Russian-English website dedicated to the writer, he summarizes his camp experiences in 46 points.

"What I Learned in the Kolyma Camps:

1. The extraordinary fragility of human nature, of civilization. A human being would turn into a beast after three weeks of hard work, cold, starvation and beatings.

2. The cold was the principal means of corrupting the soul; in the Central Asian camps people must have held out longer — it was warmer there.

3. I learned that friendship and solidarity never arise in difficult, truly severe conditions — when life is at stake. Friendship arises in difficult but bearable conditions (in the hospital, but not in the mine).

4. I learned that spite is the last human emotion to survive. A starving man has only enough flesh to feel spite — he is indifferent to everything else.

5. I learned the difference between prison, which strengthens character, and work camps, which corrupt the human soul."

“The indictment was totally extreme”

Credit: A.Savin

The Russian domestic intelligence agency FSB resides in this building in Moscow. It has served as the headquarters of the Soviet secret police since 1920. In the basement of the “Lubyanka,” as the building is called, hundreds of thousands of prisoners were interrogated and tortured and thousands were shot. The 17-year-old schoolgirl Susanna Petschuro was one of the people imprisoned there. She was sentenced to 25 years in a labor camp in 1951 for her participation in a circle of critical students. She speaks about her sentencing in a video.

"After two weeks they transferred me to the Lefortovo prison. That’s when the real prison life began. It was terrible, with endless night-time interrogations, weeks without sleep. You lose all consciousness, all orientation – it’s all over, nothing remains. When they led you through the corridors, knocking1 and turning you to the wall, one minute - in that minute you slept. During interrogation, when the interrogator wrote down my answer to a question, I slept. He would yell at me, 'You have iron nerves'. 'Well, yes.' Solitary confinement, always solitary confinement... That was the investigation. After that I was sent to the Lubyanka, then back again...

And then came the trial. The indictment was totally extreme. All the many things it contained. The trial lasted seven days. Three old people were sitting there. We each had our own guard. Of course there was neither prosecutor nor defense counsel nor witnesses. The trial took place in the cellar of the Lefortovo prison. And the pronouncement of the sentence.

After the maximum sentences2 were pronounced, everyone began to scream and cry, especially the girls. Someone shouted from the back, ‘Write a petition for pardon, write, ask for a pardon!’ Zhenya turned around and said, ‘We won't write anything, we won't ask for a pardon.’ I know they didn't write a pardon request. They refused to do that. And the others ... the three of us got ten years. My underage sister, who had not been involved in anything, and two others, Tamara Rabinovich, who had not participated anywhere, and Galya Smirnova, who knew practically nothing either. There was a remarkable phrase: 'On the grounds of a lack of a criminal offense - ten years.’"

Click here for the interview with Susanna Petschuro.

1) In Soviet prisons, when guards escorted a prisoner to interrogation, they made knocking noises to get attention and prevent inmates from running into each other.

2) Three classmates of Susanna Petschuro were sentenced to death.

Links

Video interviews with victims and witnesses of persecution in the Soviet Union (Russian, German, Italian)

Twelve part video series “Generation Gulag” (Russian with English subtitles)

Eyewitness report of the young Polish orderly Janina Perkovska