Three people light a candle at a memorial service – the Jewish women, Ela Stein-Weissberger and Inge Auerbacher, and the former American soldier Jimmy Gentry, who had helped liberate the Dachau concentration camp. Eyewitnesses like this play an important role in coming to terms with the past. There are only a few Holocaust survivors left, but many of their reports are available online. People who personally experienced the GDR continue to participate in public events.

Credit: USDAgov

“The jeering crowd stood below”

Credit: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1970-083-44 / Friedrich, H. / CC-BY-SA 3.0

On the night of November 9, the Nazi regime organized violent attacks on Jews and their property throughout Germany– like at this clothing store in Magdeburg (photo). At least 400 Jews were murdered or driven to suicide. Thousands of stores, apartments, cemeteries and synagogues were damaged or destroyed. About 30,000 Jews were subsequently sent to concentration camps. The writer, translator and librarian Josepha von Koskull witnessed the pogroms in Berlin.

“Close to the bank where I worked was the clothing district, the headquarters of Berlin’s ‘Haute Couture,’ which was very important before the war and did a lot of exporting to the Nordic countries. Most of the owners of these fashion houses were Jews. When I came out of the bank building at six o'clock, I heard wild screaming and shouting. People were plundering the fabric warehouses of the clothing stores. It made me sick, but I still had the instincts of a journalist: I had to be there when something so exciting, so unusual, was happening in Berlin.

When I think back on it today, after surviving the horrible war years in Berlin, the looting doesn’t seem so gruesome anymore, but back then it made a hellish impression. SA men threw down whole bales of cloth from the top floors – the most beautiful colorful silks blowing down like long flags in front of buildings, and the jeering crowd stood below and snatched them up. People could be seen packing the bales onto taxis and driving away with their booty. Sometimes someone would throw a bucket of water down to scatter the crowd, then the SA men threw down the typewriters, which shattered into pieces. The police stood by idly.” Read more

Links

Online Archive from the USC Shoah Foundation (registration necessary)

Video interviews from the Foundation for the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (German, registration necessary)

Biographical film interviews "Witnesses of the Shoah" (German, registration necessary)

After the Dictatorship. Instruments of Transitional Justice in Former Authoritarian Systems – An International Comparison

A project at the Department of Modern History at the University of Würzburg

Twitter: @afterdictatorship

Instagram: After the dictatorship

With financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

“I also had to go to Dr. Mengele”

Credit: Hubertus Knabe

“Arbeit macht frei” (“work makes you free”) – the Nazi’s cynical slogan still stands at the entrance to the former Auschwitz I concentration camp. Heinrich Himmler had the camp built in occupied Poland in 1940 and expanded into a huge camp complex. Approximately 1.1 million people were murdered here, including nearly 20,000 Roma and Sinti. The 92-year-old Philomena Franz describes how she arrived at the concentration camp’s so-called gypsy camp in April 1943.

“In the examination room one of the SS men said that my hair should not be shaved. My hair went down to my waist. The woman standing next to me said: ‘Hey, you’re lucky, you get to go to a brothel.’ I screamed: ‘No, I’m not going there. I’d rather die!’ Then the SS man pushed me away and a woman grabbed me and shaved off my hair.

The man who tattooed me said: ‘Such a beautiful girl, I will make you a beautiful tattoo.’ I have the number 10550. The Z stands for gypsy camp. Then I had to go to the race and clan researcher. She measured our noses, ears, eyes and said to me: ‘Run!’ Then she said: “Yes, typically Indian. The Sinti do come from India.

I also had to go to Dr. Mengele. He did the medical experiments. In one room an adult and a child were lying next to each other, and they were cut open. There were test tubes standing around with people’s parts, liver, bile. They gave me an injection, deep into my chest, I still have a scar from it. I wasn’t really conscious for two weeks.”

Click here for the Philomena Franz’s full report.

“The burning curtains flapping in the bedroom”

Credit: Deutsche Fotothek / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE

Like most German cities, Leipzig was severely destroyed during World War II by bomb attacks from the United States and Great Britain. Four years after the war, bricks from destroyed houses were still piled up in front of the St. Thomas Church, the famous workplace of Johann Sebastian Bach (photo). About 6,000 people died in the bombing. Elke Rau, a vocational school teacher describes her experience as a child during the heaviest air raid on the city.

“I was five years old in December 1943 and can only remember a few events from those early childhood days. One of them is the bombing of Leipzig on December 4, 1943, the third birthday of my younger sister, who was in bed with mumps.

My mother had baked a cake on the evening before and then waited for my father to come home from work – he was a musician, so not until 1 a.m. At about 4 o'clock, when the air-raid alarm went off, they were in their first deep sleep and didn’t hear it. I was the first to wake up and was horrified to see the burning curtains in the bedroom flapping through the broken window panes. My parents quickly wrapped us in blankets and carried us down the four flights to the air-raid shelter where the door was already locked. When we knocked loudly and in panic, the air-raid warden let us in, scolding us for being late. He was very angry when my parents asked to go back up to the apartment. All four of us were only wearing sleepwear and the carefully packed air-raid shelter suitcase was still on the 4th floor. A long 20 minutes passed before our parents were back at our sides! What we didn’t know while waiting in cellar: They had saved the house by going back upstairs. Together with a few other residents, they had been able to extinguish the fire bombs that had just hit.”

“The masses made them strong and brave”

Credit: Bundesarchiv, B 285 Bild-14676 / Unknown author / CC-BY-SA 3.0

A Soviet tank rattles through the Leipzig city center. The photo shows how Red Army units crushed the GDR uprising on June 17, 1953. A demonstration by East Berlin construction workers had triggered widespread unrest. Thousands of workers went on strike, protesting the policies of the communist regime. The teacher Wilhelm Fiebelkorn remembers the beginning and end of the uprising in the industrial city of Bitterfeld.

“But then, at about 9:30, a black wall moved forward over the railroad overpass close to our school. The workers had arrived! My heart was racing with excitement. I saw that the workers had linked arms. Everyone pulling and pushing. The connection, the masses made them strong and brave. One man stepped out in front of the black mass of people: Paul Othma. (...)

I was in a frenzy. I stood in the courtyard doorway. Students were storming out of the school. Windows were torn open. A few teachers suddenly appeared next to me. “Are we joining them?” I asked. They stood there, obviously surprised by the event, unable to say anything. Perhaps they were thinking further than I was at that moment.”

Click here for Wilhelm Fiebelkorn’s full report (in German).

Links

Eyewitness testimony on the June 17, 1953 uprising (German)

Audio and video interviews from the Foundation on the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship (German)

Oral history interviews with people who were persecuted under communism in Brandenburg (German)

Portraits of people who experienced the Berlin Wall, with excerpts from audio interviews (German)

"Open the window! Printing presses are coming!"

Credit: MfS_HA-XX_Fo-0059_Bild-0012_dd42735cf7

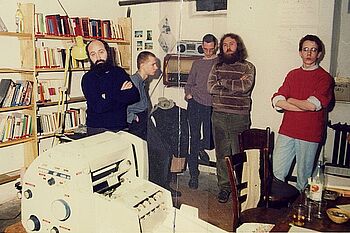

With their arms crossed in front of their chests or their hands in their pockets, five GDR opposition activists show their silent protest as they are photographed during a raid by East German secret police. In November 1987, they were printing an underground magazine when they were surprised by the Stasi. They were arrested, but released a little later following widespread protests. The printing press had been smuggled to East Berlin by a politician from the West German Green Party. In an interview, civil rights activist Stephan Bickhardt recalls how the opposition got their hands on the printer as the Stasi watched.

"Heinz Suhr was a Green Party representative in the Bundestag at the time and brought three printing presses over in his car - paid for by Jürgen Fuchs and Wolf Biermann. Then they had the great idea: ‘Come on, let’s drive by the Bickhardt’s place, they live on the first floor, so we can quickly pass the presses through the window. Then they rang my doorbell - and Wolfgang Templin [...] ran into our apartment and said: ‘Open the window! Printing presses are coming!’

And then I said: ‘Wait a minute, let me take a look at this first. When I opened the window, I saw at least 20 Stasi people hanging around in cars - Wartburgs, Trabants and many more. And then I said: “No, out of the question!”

Click here for the entire report from Stephan Bickhardt und his wife, Kathrin (in German).