The underground entrance to the Human Rights Museum of Santiago de Chile serves as an allegory for modern-day Chile: Today’s democracy emerged from the depths of a dictatorship. The museum is not the only place where victims of the military dictatorship are commemorated. Memorials have also been established at the site of former secret torture centers such as Londres 38 and Casa de José Domingo Cañas. The stadium on the west side of the capital now bears the name of the singer Victor Jara who was imprisoned there.

Museum of Memory and Human Rights

Credit: Museum of Memory and Human Rights / CC BY

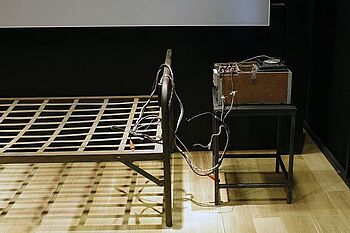

An apparatus for administering electric shocks stands next to an iron bed. The Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago de Chile documents the torture of opposition members during the Pinochet dictatorship. Opened in 2010, the museum addresses human rights violations committed in Chile under the military regime from 1973 to 1989. With its modern exhibition and architecture, it has become one of the world’s leading memorial museums.

It took more than 20 years for the Chilean state to create a central memorial for the victims of the military dictatorship. Such an institution could not even have been considered as long as the dictator Augusto Pinochet was still alive. But after his death in December 2006, the socialist president Michelle Bachelet announced plans to build a museum. A government commission drew up a concept and an architectural competition was held. The avant-garde building in the Chilean capital, designed by a Brazilian architectural firm, was officially opened by Bachelet in January 2010.

The entrance to the museum is located in the building’s lower level. Thousands of photographs of victims of the Pinochet regime hang on the front wall of an exhibition hall that extends over three floors. A map of the world shows the truth commissions of other countries and pictures of other Chilean memorials. From here, visitors can access eleven theme-based exhibition rooms dealing with the military coup on September 11, 1973, the reprisals of the junta, the Chilean resistance and the international solidarity movement. The exhibition fills a space of 5,000 square meters. The museum also contains a library, a documentation center, a memorial space and seminar rooms.

The state-financed museum is more than a commemorative history museum. Even its name reflects the political claim that extends into the present. The entrance to the museum is flanked by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The events and special exhibitions also address thematically-related subjects that go beyond the Chilean military dictatorship.

Following an earthquake that caused major damage to the exhibition, the museum was forced to close again shortly after its opening. The museum was also exposed to attacks from all sides. Conservative circles accused the museum of ignoring the causes of the military coup. Some complained that it did not mention the militancy of the left, which had initially triggered the massive military action. Victims’ associations, on the other hand, criticized the fact that the museum also commemorates members of the security forces who died during the fighting. Finally, members of the Mapuche -- an indigenous people that fiercely resisted Spanish colonization -- protested because the museum failed to address the violation of their human rights. But all of this did not detract from the success of the museum, which is visited by more than half a million people each year.

Links

Website of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights

Website of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights (Spanish)

After the Dictatorship. Instruments of Transitional Justice in Former Authoritarian Systems – An International Comparison

A project at the Department of Modern History at the University of Würzburg

Twitter: @afterdictatorship

Instagram: After the dictatorship

With financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

Villa Grimaldi Peace Park

Credit: Fotosaereas / CC BY-SA

The open space between the detached houses on the outskirts of Santiago de Chile appears out of place. The Villa Grimaldi torture center of the Chilean secret police was established behind a wall here in 1974. The property was forcibly seized from a wealthy Chilean family. With the end of the military dictatorship imminent, the state security service demolished all the buildings.

The capital department of the secret police “Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional” (DINA) raided the property shortly after the military coup. A daughter of the family was arrested. In exchange for her release, the secret police demanded the transfer of ownership of the villa. Under the name “Cuartel Terranova” (Newfoundland Barracks), it served as a command and secret interrogation center from 1974 onward.

At least 4,500 people were imprisoned here, including the future Chilean president Michelle Bachelet and her mother. Her father, an Allende-loyal general, was arrested by the military and died as a result of torture. Many prisoners were severely tortured in the Villa Grimaldi, 18 were executed and 211 are still missing. Most of the prisoners were fighters from the Movement of the Revolutionary Left (MIR), the Socialist Party of Chile (PS) and the Communist Party (PCCh).

After the dissolution of DINA in 1977, the property was handed over to the successor institution “Central Nacional de Informaciones” (CNI), which continued to use it as an interrogation center. In 1988, the secret service signed the property over to its director. That was the year the Chileans decided in a referendum that other candidates besides Pinochet could run for office in the next presidential election. All the buildings on the site were demolished and the traces of their former use were erased.

A local citizens’ initiative campaigned to preserve the site. In 1994 the transfer of ownership was reversed and the Chilean state took over the site. The former military torture site was declared a memorial -- a novelty in South America at the time.

In 1997, the Villa Grimaldi Peace Park opened on the grounds and was gradually expanded. The property was redesigned to include symbolic elements -- a spring at the intersection of pathways and a flame-shaped sculpture in front of the entrance gate. The gate and part of the enclosing wall were reconstructed. A cell was also reconstructed on the basis of eyewitness accounts and decorated with drawings by a prisoner. The names of those who were killed appear on two large walls. The villa’s restored rose garden pays tribute to the women who were persecuted. A model of the detention site and a small exhibition room are also part of the complex. In 2000, the former water tower, which had served as a single cell, was rebuilt. In 2007, a cube-shaped monument was added, incorporating sections of railway tracks. The tracks, which had been salvaged from a bay, had been used to throw the dead bodies of murdered prisoners into the sea.

Links

Website Villa Grimaldi Peace Park (Spanish)

Essay on the citizens’ initiative to establish the Villa Grimaldi Peace Park

The Valech Commission’s overview of prison sites under the military dictatorship (Spanish)

Overview of monuments for victims of human rights violations in Chile (Spanish)

Survey of memorials in Chile (Spanish)